-

1885--William Scales Accused of Rape and Lynched

1885--William Scales Accused of Rape and Lynched Upon his release from the Cincinnati Work House in 1885, where he had served a nine-month sentence for "petit larceny", William Scales returned to Boone County and found work on the farm of Samuel Hind (see 1883 Atlas segment, below). Hind had employed his mother Patsy in 1880, so this may explain William’s arrival there in 1885.

-

1884--Charles Dickerson Accused of Theft and Lynched

1884--Charles Dickerson Accused of Theft and Lynched Charles Dickerson is the youngest known victim of lynching in Boone County; he was reportedly about 17 at the time of his death, though some records place him closer to 15 years old. In 1880, Charles was living in Crittenden with Alfred and Elizabeth Lewis and is listed as a “boarder” in their home. It’s likely he was the son of Patsy Hall and Jesse Dickerson (sometimes recorded as “Dixon.”)

Charles worked for and lived on the farm of Samuel Hind in southern Boone County. His living space was located in the slave dwelling.

On February 21, 1884, Charles reportedly stole $192 from the room occupied by the elderly father of his employer and left town. He was traced to Louisville, where he had enlisted in the Army, likely as a way to evade capture and start anew. Dickerson was returned to Boone County and placed in the county jail, where he remained for more than a month.

On April 1st, Charles and two other prisoners escaped confinement. Dickerson headed to his old room at the Hind farm to change out of his uniform, which he had been wearing when captured. For another month, Charles and the two unnamed conspirators from the jail roamed the county, breaking into properties and stealing.

Merchants in Walton, fearful of the escaped convicts’ crime spree, were taking turns guarding their stores. On the evening of April 26th, Dickerson’s group broke into a store owned by J.T. Conner and found themselves under fire. The two unnamed thieves escaped, but Dickerson was trapped, hiding behind some boxes in the front of the store. He was armed and returned fire, but he got the worst of the melee.

Charles Dickerson was captured again, this time with a wound to his cheek and a slug in his leg, above the knee. He was again locked in the Burlington jail, this time in shackles. The young prisoner spent the ensuing few days amusing himself by drawing a picture of a figure hanging from a tree on the wall of the jail, perhaps to mock his would-be lynch-party. Sadly, his artwork was prophetic.

Late on Saturday evening, May 3rd, a drunken mob of about a dozen men presented themselves at jailer Samuel Cowen’s door, demanding the keys to the jail. Cowen refused, and the mob procured a sledgehammer to gain entry. The teenager was taken from the jail and hanged from the same tree on Burlington Pike that had been the site of the lynching of Smith Williams, eight years prior. Charles Dickerson’s body was taken to the Potter’s Field and buried the following day, but it was soon discovered that the body was disinterred, presumably by medical students.

Charles Dickerson’s Army enlistment papers read “Died May 3, ’84. Lynched at Burlington, Boone Co., Ky. A recruit.”

-

1880--Charles Smith Accused of Arson and Lynched

1880--Charles Smith Accused of Arson and Lynched Charles Smith was one of many prisoners in the Kentucky State Penitentiary who received a pardon from Governor Blackburn in 1879. During this period, Kentucky’s prison system was badly in need of reform and was subject to overcrowding resulting in inhumane living conditions. Gov. Blackburn was a physician who made this his signature program immediately upon taking office.

-

1879--Theodore Daniels Accused of Assault and Lynched

1879--Theodore Daniels Accused of Assault and Lynched Very little is known about the life of Theodore Daniels. To date, no one of this name or similar names has been found in the 1870 census. Due to the fluid nature of African American surnames during this period, combined with record-keeping problems, it’s possible he was missed or his name entered differently in official records. There were numerous African Americans in the counties adjacent to Boone with the surname “Daniels” in the 1870 census; a possible connection.

A woman named Fanny Daniels was living in Cincinnati in 1870, according to the census that year. She was born in Kentucky and lived with several daughters and a man named George Frazier. Later census records show her living with family members named “Huey.” Both the Huey and Frazier names appear in the Union area of Boone County and several of these families held enslaved people prior to the end of the Civil War; it’s possible there is a family connection between Fanny and Theodore Daniels and the appearance of these other names in Fanny’s circle may explain why Theodore was working in the Union area.

Theodore Daniels worked as a laborer on the farm of Fielding Dickey, who owned a large amount of property on U. S. 42, near Union. On September 3, 1879, Daniels was accused of the attempted rape of the adopted daughter of Dickey, a 15-year old girl named Georgia Billiter.

Theodore Daniels was mis-identified in news accounts as “Willis Jackson” and his alleged victim, Georgia Billiter was also mis-identified as “Ella Kearney.” These names appear in Jefferson County, Kentucky records, so it’s possible another incident was confused with the events in Boone County, around the same time.

Daniels escaped immediate capture, but was caught near the Kenton County line and returned to the Union town hall. Mr. Dickey was prevented from shooting Daniels upon his return, but local tensions ran high, and the constables were unable to protect their prisoner from the mob and allow justice to proceed.

The planned transfer of Daniels to the county seat never occurred. The men guarding Daniels were outnumbered by a mob that had gathered in the night. The mob forcibly took Daniels out of the hands of officials to a location on the outskirts of town. Once at the chosen destination, Daniels was tied to a tree and shot; the members of the mob were never identified.

-

1877--Parker Mayo Accused of Assault and Lynched

1877--Parker Mayo Accused of Assault and Lynched Parker Mayo was born in Manakin-Sabot, Goochland County, Virginia, enslaved by a man named William Diedrick. Diedrick’s plantation, known as “Rochambeau” was comprised of over 600 acres. There was a grist mill, saw mill and blacksmith shop on site and Diedrick may have been operating a mercantile on the property at one point as well. In 1850, he held 11 enslaved people; by 1860 that number was reduced to six. Among those enslaved in 1860, was a seven-year old boy; it’s likely that this boy was Parker Mayo. The Mayo name is found among several African American families in Goochland County in census records of 1870.

The Diedrick home is still standing and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1999. It resembles Boone County’s own Dinsmore homestead.

Based on the ages of the enslaved people held by Diedrick in 1860, it’s possible that Parker’s parents were John and Mary Mayo, who lived nearby the Diedrick farm in 1870. Parker’s name does not appear in the household that year, but there are several other children. It’s possible Parker, who was a teen at the time, was working as a laborer elsewhere and did not get recorded on the census records.

Sometime around 1875, Mayo had made his way to Walton, where he was working sporadically on the construction of the Louisville Short Line railway. Another railroad worker, James Murray, who was white, lived in a shanty just north of the crossing of the Louisville Short Line and the Cincinnati Southern railroad tracks with his wife and several children. In late March, 1877, Murray and his wife took their youngest for treatment at St. Elizabeth Hospital in Covington, leaving their nine-year old daughter, Molly and two other children alone in the shack.

It was alleged that during the absence of James and his wife, Mayo entered their home and raped Molly. It was reported that sometime after the assault, he tried to entice her into the woods to kill her, but the girl refused to go with him. Mayo was next accused of going to the nearby cabin of Mr. Shefly, a tenant farmer on the property of George Gaines where he encountered the man’s wife, who claimed Mayo was armed and threatened her.

Groups of men were dispatched to hunt Mayo down. Mr. Shefly and an acquaintance were looking in the Florence area and decided to rest for the night upon a stack of hay. They claimed to have discovered Parker Mayo sleeping the very haystack they had chosen to rest upon. The Florence constable was summoned and Mayo was arrested. He was taken to Walton before the magistrates and witnesses were brought to testify; bail was set at $500.

On May 29th, 1877, Mayo was being transported in an open-topped wagon to the Boone County Jail in Burlington, in the custody of two officers. The wagon was accosted just outside of Walton, near James Murray’s shack, by a large group of unnamed men. The men took Parker Mayo out of the wagon and the officers fled. Parker Mayo’s body was discovered hanging from a tree just west of the Lexington Pike, two miles outside Walton; the body was buried within one hundred yards of the hanging tree.

-

1876--Smith Williams Taken from Jail and Lynched

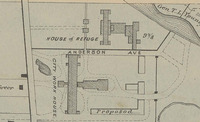

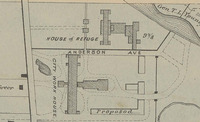

1876--Smith Williams Taken from Jail and Lynched Little is known about the early life of Smith Williams. He was born somewhere in Kentucky around 1843 and in 1870 Williams was living with his wife, Melinda, and their ten-month-old daughter, Kate, in Covington. According to the census record of that year, Smith Williams worked as a general laborer. Like many African Americans in the region, he may have come to town in search of work to support himself and his family after the Civil War. In 1871, Smith Williams appeared in the Covington, KY City Directory, listed again as a laborer. He was living at 715 Willard Street, between Seventh and Eighth streets, not far from Covington’s Main Strasse neighborhood. It’s likely he rented an apartment for his family in the multi-family building (see image).

Smith and his family moved to Boone County soon after, where his name appears on the county tax lists from 1872-1874. On July 1, 1875, Smith was working on a farm in the village of Constance, not far from the Anderson Ferry on the Ohio River. A group of hunters were crossing the property where he worked and Williams fired upon them with his rifle. One man was wounded; a young white man named Frederick Wahl, who lived in Constance with his parents and siblings. There was speculation that Williams fired upon Wahl for trespassing, though it’s not clear what provoked the action. Wahl died of his wounds within a few days and Williams fled the area, fearing for his own life.

In early March, 1876, brothers Eph and Montgomery Anderson, Constance residents, arrived in Indianapolis. They had received word that Smith Williams was living there under the alias “Enos Thompson” and they had come seeking justice for Fred Wahl’s death. The men summoned local authorities who went to make the arrest. As an officer arrived to capture Williams, he put up a great struggle, but was ultimately apprehended and returned to the Burlington Jail to await arraignment, his bond set at $1000

Williams expressed the very rational fear of being forcibly taken from his cell by a mob of vigilantes to Samuel Cowan, the county jailer. There had never been a lynching in Boone County at that time, so it’s possible the jailer believed all was secure and the rule of law would prevail. Smith languished in his cell for weeks awaiting trial, kept company by several other prisoners. Late in the third week of June, 1876, the last remaining prisoner was released, leaving Williams alone and vulnerable.

Samuel Cowan lived just across the road from the small jail; but it’s likely that Williams was alone in the building on the night of June 22nd when a large, angry mob arrived at about 1 AM. Several of the group roused the jailer, claiming to have a prisoner that needed to be locked up. As Cowan emerged from his home, keys in hand, he was accosted, a hand placed over his mouth and the keys forcibly taken from him.

When the men reached Williams’ cell door, the prisoner began to scream “Fire! Murder!” and hollered for the jailer, Cowan, who was being held by some of the mob, unable to come to his aid. Williams broke away and got as far as the southwest corner of the courthouse before he was overtaken. Men were shouting and shooting their pistols in the air as the scene intensified. The commotion was loud enough for Melinda Williams to hear from the home where she worked and lived with their young daughter Katie, just about a block away.

As the angry mob caught up with Williams, he was struck in the head with a hammer of the style used for cutting iron. The hammer, later found near the scene, was stamped with “I. & C.R.R.” indicating it was the property of the Indianapolis and Cincinnati Railroad Company. Smith was badly wounded and it was later determined that, among the many injuries to his body, he had several large gashes in his head and a fractured skull, doubtless from the blows of the hammer.

The mob’s intent was to hang Smith Williams where they first detained him, within view of the courtroom where he was to be tried by law for the charge against him. Calls for a rope by the mob went unanswered, so they took their victim, loaded him in a wagon and headed off in the direction of Florence to complete their dark goal. The shouts of the mob, mingled with sounds of gunshots and Smith’s agonized cries began to fade into the distance as a frantic Melinda Williams came running to the scene from the home of her employer, within earshot of the courthouse square. The sight of her husband being hauled away to his death was her last glimpse of him alive.

The following morning, travelers down Burlington Pike were greeted by the horrific sight of the body of Smith Williams, hanging from a walnut tree, his hands and feet bound. An inquest was held and the body was examined. The foreman of the jury summoned to the scene was none other than Noah Craven, whose farm was the likely site of the lynching.

Smith Williams’ body was washed, dressed and interred in the Pauper’s cemetery. Sometime in the years after the loss of her husband, Melinda remarried. She and Kate, the daughter she shared with Smith Williams, appear in the 1880 census with her second husband, Walker Gaines. None of the members of the lynch mob were ever identified.

-

1876--Joe Payne Accused of Assault and Murdered by Mob

In the 1870s, expansion of the rail system offered ample opportunities for laborers. The Cincinnati Southern Railway was rapidly expanding in the mid-1870s. Around this time a man named Joe Payne was employed on the railroad crew. There is no information to indicate where he was from, only that he ended up working first for the railroad and later for local Boone County farmers. One of the men who employed him was Jacob Scott who owned a farm near the town center of Union.

The summer of 1876 brought the first recorded lynching to Boone County. This dark milestone in county history involved Smith Williams, who had been forcibly taken from the Burlington Jail by an angry mob and hanged early in the morning of June 23rd. The news of this violent act was well-known throughout the county and region. African Americans in Boone County were left fearful in the aftermath of this murder, but another episode of mob justice was on the horizon.

One week following the lynching of Smith Williams, Joe Payne was accused of the assaulting a daughter of Jacob Scott. The reports indicate that Sallie Scott was asleep in her room, along with a friend who had come to spend the night. Joe Payne, stark naked at the time, reportedly entered the room where the girls slept and tried to forcibly carry Sallie away. Her screams alerted the family and Payne fled. The next morning, he was discovered in the barn of a former employer, Marion Stephens, over six miles away. Stephens supplied him with clothing after Payne explained his had been ripped and taken during a fight with other railroad workers. By chance two of Stephens’ acquaintances passing by his farm had told of the events in Union; Stephens turned Payne over to the men.

Joe Payne was taken back to the Union town hall and charged before being transported under guard to Burlington. Along the way to Burlington, masked men accosted the group and shot Payne on site. His body was left in the woods near the Forks of Gunpowder Church, currently just off Pleasant Valley Road. An inquest was held and it was determined that he died of gunshot wounds: several to the head and torso. His cause of death was murder by unknown perpetrators.

Jacob Scott and his family sold their farm in Union and left for Kansas sometime before 1880.

1885--William Scales Accused of Rape and Lynched Upon his release from the Cincinnati Work House in 1885, where he had served a nine-month sentence for "petit larceny", William Scales returned to Boone County and found work on the farm of Samuel Hind (see 1883 Atlas segment, below). Hind had employed his mother Patsy in 1880, so this may explain William’s arrival there in 1885.

1885--William Scales Accused of Rape and Lynched Upon his release from the Cincinnati Work House in 1885, where he had served a nine-month sentence for "petit larceny", William Scales returned to Boone County and found work on the farm of Samuel Hind (see 1883 Atlas segment, below). Hind had employed his mother Patsy in 1880, so this may explain William’s arrival there in 1885. 1884--Charles Dickerson Accused of Theft and Lynched Charles Dickerson is the youngest known victim of lynching in Boone County; he was reportedly about 17 at the time of his death, though some records place him closer to 15 years old. In 1880, Charles was living in Crittenden with Alfred and Elizabeth Lewis and is listed as a “boarder” in their home. It’s likely he was the son of Patsy Hall and Jesse Dickerson (sometimes recorded as “Dixon.”) Charles worked for and lived on the farm of Samuel Hind in southern Boone County. His living space was located in the slave dwelling. On February 21, 1884, Charles reportedly stole $192 from the room occupied by the elderly father of his employer and left town. He was traced to Louisville, where he had enlisted in the Army, likely as a way to evade capture and start anew. Dickerson was returned to Boone County and placed in the county jail, where he remained for more than a month. On April 1st, Charles and two other prisoners escaped confinement. Dickerson headed to his old room at the Hind farm to change out of his uniform, which he had been wearing when captured. For another month, Charles and the two unnamed conspirators from the jail roamed the county, breaking into properties and stealing. Merchants in Walton, fearful of the escaped convicts’ crime spree, were taking turns guarding their stores. On the evening of April 26th, Dickerson’s group broke into a store owned by J.T. Conner and found themselves under fire. The two unnamed thieves escaped, but Dickerson was trapped, hiding behind some boxes in the front of the store. He was armed and returned fire, but he got the worst of the melee. Charles Dickerson was captured again, this time with a wound to his cheek and a slug in his leg, above the knee. He was again locked in the Burlington jail, this time in shackles. The young prisoner spent the ensuing few days amusing himself by drawing a picture of a figure hanging from a tree on the wall of the jail, perhaps to mock his would-be lynch-party. Sadly, his artwork was prophetic. Late on Saturday evening, May 3rd, a drunken mob of about a dozen men presented themselves at jailer Samuel Cowen’s door, demanding the keys to the jail. Cowen refused, and the mob procured a sledgehammer to gain entry. The teenager was taken from the jail and hanged from the same tree on Burlington Pike that had been the site of the lynching of Smith Williams, eight years prior. Charles Dickerson’s body was taken to the Potter’s Field and buried the following day, but it was soon discovered that the body was disinterred, presumably by medical students. Charles Dickerson’s Army enlistment papers read “Died May 3, ’84. Lynched at Burlington, Boone Co., Ky. A recruit.”

1884--Charles Dickerson Accused of Theft and Lynched Charles Dickerson is the youngest known victim of lynching in Boone County; he was reportedly about 17 at the time of his death, though some records place him closer to 15 years old. In 1880, Charles was living in Crittenden with Alfred and Elizabeth Lewis and is listed as a “boarder” in their home. It’s likely he was the son of Patsy Hall and Jesse Dickerson (sometimes recorded as “Dixon.”) Charles worked for and lived on the farm of Samuel Hind in southern Boone County. His living space was located in the slave dwelling. On February 21, 1884, Charles reportedly stole $192 from the room occupied by the elderly father of his employer and left town. He was traced to Louisville, where he had enlisted in the Army, likely as a way to evade capture and start anew. Dickerson was returned to Boone County and placed in the county jail, where he remained for more than a month. On April 1st, Charles and two other prisoners escaped confinement. Dickerson headed to his old room at the Hind farm to change out of his uniform, which he had been wearing when captured. For another month, Charles and the two unnamed conspirators from the jail roamed the county, breaking into properties and stealing. Merchants in Walton, fearful of the escaped convicts’ crime spree, were taking turns guarding their stores. On the evening of April 26th, Dickerson’s group broke into a store owned by J.T. Conner and found themselves under fire. The two unnamed thieves escaped, but Dickerson was trapped, hiding behind some boxes in the front of the store. He was armed and returned fire, but he got the worst of the melee. Charles Dickerson was captured again, this time with a wound to his cheek and a slug in his leg, above the knee. He was again locked in the Burlington jail, this time in shackles. The young prisoner spent the ensuing few days amusing himself by drawing a picture of a figure hanging from a tree on the wall of the jail, perhaps to mock his would-be lynch-party. Sadly, his artwork was prophetic. Late on Saturday evening, May 3rd, a drunken mob of about a dozen men presented themselves at jailer Samuel Cowen’s door, demanding the keys to the jail. Cowen refused, and the mob procured a sledgehammer to gain entry. The teenager was taken from the jail and hanged from the same tree on Burlington Pike that had been the site of the lynching of Smith Williams, eight years prior. Charles Dickerson’s body was taken to the Potter’s Field and buried the following day, but it was soon discovered that the body was disinterred, presumably by medical students. Charles Dickerson’s Army enlistment papers read “Died May 3, ’84. Lynched at Burlington, Boone Co., Ky. A recruit.” 1880--Charles Smith Accused of Arson and Lynched Charles Smith was one of many prisoners in the Kentucky State Penitentiary who received a pardon from Governor Blackburn in 1879. During this period, Kentucky’s prison system was badly in need of reform and was subject to overcrowding resulting in inhumane living conditions. Gov. Blackburn was a physician who made this his signature program immediately upon taking office.

1880--Charles Smith Accused of Arson and Lynched Charles Smith was one of many prisoners in the Kentucky State Penitentiary who received a pardon from Governor Blackburn in 1879. During this period, Kentucky’s prison system was badly in need of reform and was subject to overcrowding resulting in inhumane living conditions. Gov. Blackburn was a physician who made this his signature program immediately upon taking office. 1879--Theodore Daniels Accused of Assault and Lynched Very little is known about the life of Theodore Daniels. To date, no one of this name or similar names has been found in the 1870 census. Due to the fluid nature of African American surnames during this period, combined with record-keeping problems, it’s possible he was missed or his name entered differently in official records. There were numerous African Americans in the counties adjacent to Boone with the surname “Daniels” in the 1870 census; a possible connection. A woman named Fanny Daniels was living in Cincinnati in 1870, according to the census that year. She was born in Kentucky and lived with several daughters and a man named George Frazier. Later census records show her living with family members named “Huey.” Both the Huey and Frazier names appear in the Union area of Boone County and several of these families held enslaved people prior to the end of the Civil War; it’s possible there is a family connection between Fanny and Theodore Daniels and the appearance of these other names in Fanny’s circle may explain why Theodore was working in the Union area. Theodore Daniels worked as a laborer on the farm of Fielding Dickey, who owned a large amount of property on U. S. 42, near Union. On September 3, 1879, Daniels was accused of the attempted rape of the adopted daughter of Dickey, a 15-year old girl named Georgia Billiter. Theodore Daniels was mis-identified in news accounts as “Willis Jackson” and his alleged victim, Georgia Billiter was also mis-identified as “Ella Kearney.” These names appear in Jefferson County, Kentucky records, so it’s possible another incident was confused with the events in Boone County, around the same time. Daniels escaped immediate capture, but was caught near the Kenton County line and returned to the Union town hall. Mr. Dickey was prevented from shooting Daniels upon his return, but local tensions ran high, and the constables were unable to protect their prisoner from the mob and allow justice to proceed. The planned transfer of Daniels to the county seat never occurred. The men guarding Daniels were outnumbered by a mob that had gathered in the night. The mob forcibly took Daniels out of the hands of officials to a location on the outskirts of town. Once at the chosen destination, Daniels was tied to a tree and shot; the members of the mob were never identified.

1879--Theodore Daniels Accused of Assault and Lynched Very little is known about the life of Theodore Daniels. To date, no one of this name or similar names has been found in the 1870 census. Due to the fluid nature of African American surnames during this period, combined with record-keeping problems, it’s possible he was missed or his name entered differently in official records. There were numerous African Americans in the counties adjacent to Boone with the surname “Daniels” in the 1870 census; a possible connection. A woman named Fanny Daniels was living in Cincinnati in 1870, according to the census that year. She was born in Kentucky and lived with several daughters and a man named George Frazier. Later census records show her living with family members named “Huey.” Both the Huey and Frazier names appear in the Union area of Boone County and several of these families held enslaved people prior to the end of the Civil War; it’s possible there is a family connection between Fanny and Theodore Daniels and the appearance of these other names in Fanny’s circle may explain why Theodore was working in the Union area. Theodore Daniels worked as a laborer on the farm of Fielding Dickey, who owned a large amount of property on U. S. 42, near Union. On September 3, 1879, Daniels was accused of the attempted rape of the adopted daughter of Dickey, a 15-year old girl named Georgia Billiter. Theodore Daniels was mis-identified in news accounts as “Willis Jackson” and his alleged victim, Georgia Billiter was also mis-identified as “Ella Kearney.” These names appear in Jefferson County, Kentucky records, so it’s possible another incident was confused with the events in Boone County, around the same time. Daniels escaped immediate capture, but was caught near the Kenton County line and returned to the Union town hall. Mr. Dickey was prevented from shooting Daniels upon his return, but local tensions ran high, and the constables were unable to protect their prisoner from the mob and allow justice to proceed. The planned transfer of Daniels to the county seat never occurred. The men guarding Daniels were outnumbered by a mob that had gathered in the night. The mob forcibly took Daniels out of the hands of officials to a location on the outskirts of town. Once at the chosen destination, Daniels was tied to a tree and shot; the members of the mob were never identified. 1877--Parker Mayo Accused of Assault and Lynched Parker Mayo was born in Manakin-Sabot, Goochland County, Virginia, enslaved by a man named William Diedrick. Diedrick’s plantation, known as “Rochambeau” was comprised of over 600 acres. There was a grist mill, saw mill and blacksmith shop on site and Diedrick may have been operating a mercantile on the property at one point as well. In 1850, he held 11 enslaved people; by 1860 that number was reduced to six. Among those enslaved in 1860, was a seven-year old boy; it’s likely that this boy was Parker Mayo. The Mayo name is found among several African American families in Goochland County in census records of 1870. The Diedrick home is still standing and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1999. It resembles Boone County’s own Dinsmore homestead. Based on the ages of the enslaved people held by Diedrick in 1860, it’s possible that Parker’s parents were John and Mary Mayo, who lived nearby the Diedrick farm in 1870. Parker’s name does not appear in the household that year, but there are several other children. It’s possible Parker, who was a teen at the time, was working as a laborer elsewhere and did not get recorded on the census records. Sometime around 1875, Mayo had made his way to Walton, where he was working sporadically on the construction of the Louisville Short Line railway. Another railroad worker, James Murray, who was white, lived in a shanty just north of the crossing of the Louisville Short Line and the Cincinnati Southern railroad tracks with his wife and several children. In late March, 1877, Murray and his wife took their youngest for treatment at St. Elizabeth Hospital in Covington, leaving their nine-year old daughter, Molly and two other children alone in the shack. It was alleged that during the absence of James and his wife, Mayo entered their home and raped Molly. It was reported that sometime after the assault, he tried to entice her into the woods to kill her, but the girl refused to go with him. Mayo was next accused of going to the nearby cabin of Mr. Shefly, a tenant farmer on the property of George Gaines where he encountered the man’s wife, who claimed Mayo was armed and threatened her. Groups of men were dispatched to hunt Mayo down. Mr. Shefly and an acquaintance were looking in the Florence area and decided to rest for the night upon a stack of hay. They claimed to have discovered Parker Mayo sleeping the very haystack they had chosen to rest upon. The Florence constable was summoned and Mayo was arrested. He was taken to Walton before the magistrates and witnesses were brought to testify; bail was set at $500. On May 29th, 1877, Mayo was being transported in an open-topped wagon to the Boone County Jail in Burlington, in the custody of two officers. The wagon was accosted just outside of Walton, near James Murray’s shack, by a large group of unnamed men. The men took Parker Mayo out of the wagon and the officers fled. Parker Mayo’s body was discovered hanging from a tree just west of the Lexington Pike, two miles outside Walton; the body was buried within one hundred yards of the hanging tree.

1877--Parker Mayo Accused of Assault and Lynched Parker Mayo was born in Manakin-Sabot, Goochland County, Virginia, enslaved by a man named William Diedrick. Diedrick’s plantation, known as “Rochambeau” was comprised of over 600 acres. There was a grist mill, saw mill and blacksmith shop on site and Diedrick may have been operating a mercantile on the property at one point as well. In 1850, he held 11 enslaved people; by 1860 that number was reduced to six. Among those enslaved in 1860, was a seven-year old boy; it’s likely that this boy was Parker Mayo. The Mayo name is found among several African American families in Goochland County in census records of 1870. The Diedrick home is still standing and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1999. It resembles Boone County’s own Dinsmore homestead. Based on the ages of the enslaved people held by Diedrick in 1860, it’s possible that Parker’s parents were John and Mary Mayo, who lived nearby the Diedrick farm in 1870. Parker’s name does not appear in the household that year, but there are several other children. It’s possible Parker, who was a teen at the time, was working as a laborer elsewhere and did not get recorded on the census records. Sometime around 1875, Mayo had made his way to Walton, where he was working sporadically on the construction of the Louisville Short Line railway. Another railroad worker, James Murray, who was white, lived in a shanty just north of the crossing of the Louisville Short Line and the Cincinnati Southern railroad tracks with his wife and several children. In late March, 1877, Murray and his wife took their youngest for treatment at St. Elizabeth Hospital in Covington, leaving their nine-year old daughter, Molly and two other children alone in the shack. It was alleged that during the absence of James and his wife, Mayo entered their home and raped Molly. It was reported that sometime after the assault, he tried to entice her into the woods to kill her, but the girl refused to go with him. Mayo was next accused of going to the nearby cabin of Mr. Shefly, a tenant farmer on the property of George Gaines where he encountered the man’s wife, who claimed Mayo was armed and threatened her. Groups of men were dispatched to hunt Mayo down. Mr. Shefly and an acquaintance were looking in the Florence area and decided to rest for the night upon a stack of hay. They claimed to have discovered Parker Mayo sleeping the very haystack they had chosen to rest upon. The Florence constable was summoned and Mayo was arrested. He was taken to Walton before the magistrates and witnesses were brought to testify; bail was set at $500. On May 29th, 1877, Mayo was being transported in an open-topped wagon to the Boone County Jail in Burlington, in the custody of two officers. The wagon was accosted just outside of Walton, near James Murray’s shack, by a large group of unnamed men. The men took Parker Mayo out of the wagon and the officers fled. Parker Mayo’s body was discovered hanging from a tree just west of the Lexington Pike, two miles outside Walton; the body was buried within one hundred yards of the hanging tree. 1876--Smith Williams Taken from Jail and Lynched Little is known about the early life of Smith Williams. He was born somewhere in Kentucky around 1843 and in 1870 Williams was living with his wife, Melinda, and their ten-month-old daughter, Kate, in Covington. According to the census record of that year, Smith Williams worked as a general laborer. Like many African Americans in the region, he may have come to town in search of work to support himself and his family after the Civil War. In 1871, Smith Williams appeared in the Covington, KY City Directory, listed again as a laborer. He was living at 715 Willard Street, between Seventh and Eighth streets, not far from Covington’s Main Strasse neighborhood. It’s likely he rented an apartment for his family in the multi-family building (see image). Smith and his family moved to Boone County soon after, where his name appears on the county tax lists from 1872-1874. On July 1, 1875, Smith was working on a farm in the village of Constance, not far from the Anderson Ferry on the Ohio River. A group of hunters were crossing the property where he worked and Williams fired upon them with his rifle. One man was wounded; a young white man named Frederick Wahl, who lived in Constance with his parents and siblings. There was speculation that Williams fired upon Wahl for trespassing, though it’s not clear what provoked the action. Wahl died of his wounds within a few days and Williams fled the area, fearing for his own life. In early March, 1876, brothers Eph and Montgomery Anderson, Constance residents, arrived in Indianapolis. They had received word that Smith Williams was living there under the alias “Enos Thompson” and they had come seeking justice for Fred Wahl’s death. The men summoned local authorities who went to make the arrest. As an officer arrived to capture Williams, he put up a great struggle, but was ultimately apprehended and returned to the Burlington Jail to await arraignment, his bond set at $1000 Williams expressed the very rational fear of being forcibly taken from his cell by a mob of vigilantes to Samuel Cowan, the county jailer. There had never been a lynching in Boone County at that time, so it’s possible the jailer believed all was secure and the rule of law would prevail. Smith languished in his cell for weeks awaiting trial, kept company by several other prisoners. Late in the third week of June, 1876, the last remaining prisoner was released, leaving Williams alone and vulnerable. Samuel Cowan lived just across the road from the small jail; but it’s likely that Williams was alone in the building on the night of June 22nd when a large, angry mob arrived at about 1 AM. Several of the group roused the jailer, claiming to have a prisoner that needed to be locked up. As Cowan emerged from his home, keys in hand, he was accosted, a hand placed over his mouth and the keys forcibly taken from him. When the men reached Williams’ cell door, the prisoner began to scream “Fire! Murder!” and hollered for the jailer, Cowan, who was being held by some of the mob, unable to come to his aid. Williams broke away and got as far as the southwest corner of the courthouse before he was overtaken. Men were shouting and shooting their pistols in the air as the scene intensified. The commotion was loud enough for Melinda Williams to hear from the home where she worked and lived with their young daughter Katie, just about a block away. As the angry mob caught up with Williams, he was struck in the head with a hammer of the style used for cutting iron. The hammer, later found near the scene, was stamped with “I. & C.R.R.” indicating it was the property of the Indianapolis and Cincinnati Railroad Company. Smith was badly wounded and it was later determined that, among the many injuries to his body, he had several large gashes in his head and a fractured skull, doubtless from the blows of the hammer. The mob’s intent was to hang Smith Williams where they first detained him, within view of the courtroom where he was to be tried by law for the charge against him. Calls for a rope by the mob went unanswered, so they took their victim, loaded him in a wagon and headed off in the direction of Florence to complete their dark goal. The shouts of the mob, mingled with sounds of gunshots and Smith’s agonized cries began to fade into the distance as a frantic Melinda Williams came running to the scene from the home of her employer, within earshot of the courthouse square. The sight of her husband being hauled away to his death was her last glimpse of him alive. The following morning, travelers down Burlington Pike were greeted by the horrific sight of the body of Smith Williams, hanging from a walnut tree, his hands and feet bound. An inquest was held and the body was examined. The foreman of the jury summoned to the scene was none other than Noah Craven, whose farm was the likely site of the lynching. Smith Williams’ body was washed, dressed and interred in the Pauper’s cemetery. Sometime in the years after the loss of her husband, Melinda remarried. She and Kate, the daughter she shared with Smith Williams, appear in the 1880 census with her second husband, Walker Gaines. None of the members of the lynch mob were ever identified.

1876--Smith Williams Taken from Jail and Lynched Little is known about the early life of Smith Williams. He was born somewhere in Kentucky around 1843 and in 1870 Williams was living with his wife, Melinda, and their ten-month-old daughter, Kate, in Covington. According to the census record of that year, Smith Williams worked as a general laborer. Like many African Americans in the region, he may have come to town in search of work to support himself and his family after the Civil War. In 1871, Smith Williams appeared in the Covington, KY City Directory, listed again as a laborer. He was living at 715 Willard Street, between Seventh and Eighth streets, not far from Covington’s Main Strasse neighborhood. It’s likely he rented an apartment for his family in the multi-family building (see image). Smith and his family moved to Boone County soon after, where his name appears on the county tax lists from 1872-1874. On July 1, 1875, Smith was working on a farm in the village of Constance, not far from the Anderson Ferry on the Ohio River. A group of hunters were crossing the property where he worked and Williams fired upon them with his rifle. One man was wounded; a young white man named Frederick Wahl, who lived in Constance with his parents and siblings. There was speculation that Williams fired upon Wahl for trespassing, though it’s not clear what provoked the action. Wahl died of his wounds within a few days and Williams fled the area, fearing for his own life. In early March, 1876, brothers Eph and Montgomery Anderson, Constance residents, arrived in Indianapolis. They had received word that Smith Williams was living there under the alias “Enos Thompson” and they had come seeking justice for Fred Wahl’s death. The men summoned local authorities who went to make the arrest. As an officer arrived to capture Williams, he put up a great struggle, but was ultimately apprehended and returned to the Burlington Jail to await arraignment, his bond set at $1000 Williams expressed the very rational fear of being forcibly taken from his cell by a mob of vigilantes to Samuel Cowan, the county jailer. There had never been a lynching in Boone County at that time, so it’s possible the jailer believed all was secure and the rule of law would prevail. Smith languished in his cell for weeks awaiting trial, kept company by several other prisoners. Late in the third week of June, 1876, the last remaining prisoner was released, leaving Williams alone and vulnerable. Samuel Cowan lived just across the road from the small jail; but it’s likely that Williams was alone in the building on the night of June 22nd when a large, angry mob arrived at about 1 AM. Several of the group roused the jailer, claiming to have a prisoner that needed to be locked up. As Cowan emerged from his home, keys in hand, he was accosted, a hand placed over his mouth and the keys forcibly taken from him. When the men reached Williams’ cell door, the prisoner began to scream “Fire! Murder!” and hollered for the jailer, Cowan, who was being held by some of the mob, unable to come to his aid. Williams broke away and got as far as the southwest corner of the courthouse before he was overtaken. Men were shouting and shooting their pistols in the air as the scene intensified. The commotion was loud enough for Melinda Williams to hear from the home where she worked and lived with their young daughter Katie, just about a block away. As the angry mob caught up with Williams, he was struck in the head with a hammer of the style used for cutting iron. The hammer, later found near the scene, was stamped with “I. & C.R.R.” indicating it was the property of the Indianapolis and Cincinnati Railroad Company. Smith was badly wounded and it was later determined that, among the many injuries to his body, he had several large gashes in his head and a fractured skull, doubtless from the blows of the hammer. The mob’s intent was to hang Smith Williams where they first detained him, within view of the courtroom where he was to be tried by law for the charge against him. Calls for a rope by the mob went unanswered, so they took their victim, loaded him in a wagon and headed off in the direction of Florence to complete their dark goal. The shouts of the mob, mingled with sounds of gunshots and Smith’s agonized cries began to fade into the distance as a frantic Melinda Williams came running to the scene from the home of her employer, within earshot of the courthouse square. The sight of her husband being hauled away to his death was her last glimpse of him alive. The following morning, travelers down Burlington Pike were greeted by the horrific sight of the body of Smith Williams, hanging from a walnut tree, his hands and feet bound. An inquest was held and the body was examined. The foreman of the jury summoned to the scene was none other than Noah Craven, whose farm was the likely site of the lynching. Smith Williams’ body was washed, dressed and interred in the Pauper’s cemetery. Sometime in the years after the loss of her husband, Melinda remarried. She and Kate, the daughter she shared with Smith Williams, appear in the 1880 census with her second husband, Walker Gaines. None of the members of the lynch mob were ever identified.